A Local-First Case Study

I just got back from a travel sabbatical. While the trip turned out great, the planning process was decidedly… less so. Figuring out six months of travel is a daunting task, and I quickly became dissatisfied with existing tools.

True to myself, I yak shaved the problem.

Introducing Waypoint waypoint.jakelazaroff.com : a local-first web app for planning trips!

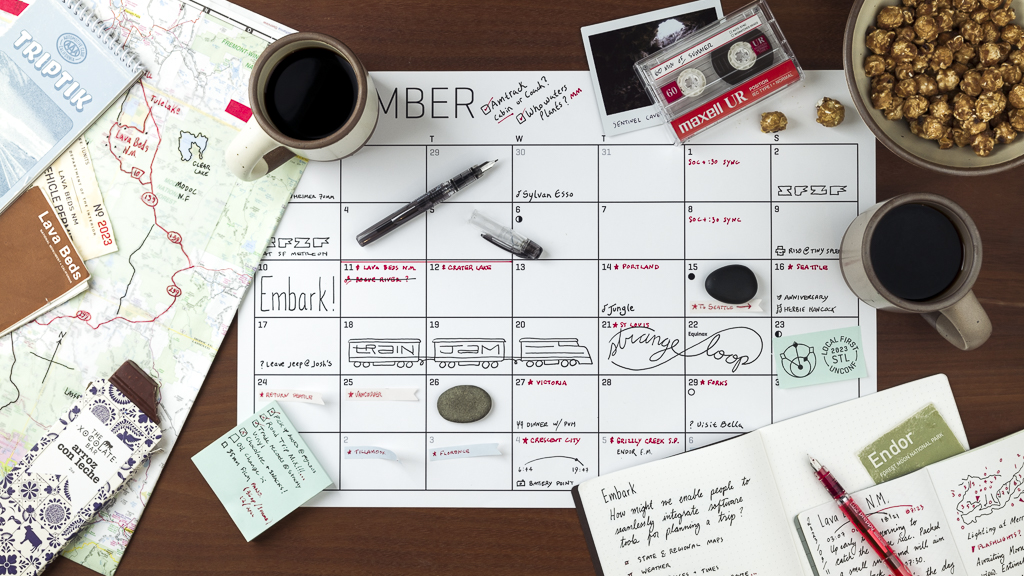

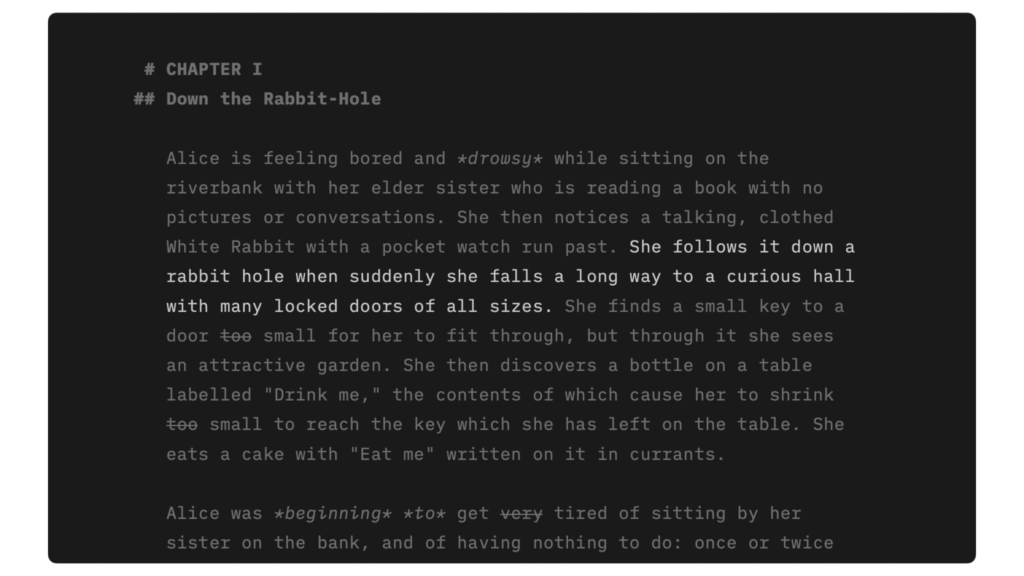

You might be thinking “hey, that looks a lot like that trip planning app Ink & Switch built  Embark: Dynamic documents for making plans Gradually enriching a text outline with travel planning tools

Embark: Dynamic documents for making plans Gradually enriching a text outline with travel planning tools www.inkandswitch.com/embark/ ”, and you’d be right: Embark was the single biggest influence on Waypoint.

In fact, Embark is even more ambitious — pulling in data like weather forecasts, embedding arbitrary views like calendars and introducing a new formula language for live calculations.

I highly recommend reading their writeup!

But Ink & Switch didn’t make Embark public, and I needed to plan a long trip, so here we are.

I want to talk about three things: the big ideas behind Waypoint, how I actually built it and what I learned.

(Quick disclaimer: Waypoint is not — and probably will never be — production-ready software. I built it to fit my exact needs while planning this trip. There are rough edges, missing features and bugs. There’s no authentication. I’m sharing it because I think it’s a useful case study in building an actual local-first app, not because I’m trying to dethrone Google Maps.)

Why I Built Waypoint

I tried a few existing tools before deciding to build my own. Apple Notes was too spartan, Notion and Google Maps were too clunky and Wanderlog was much too structured to use for research and exploration.1: In every tool, it was either difficult to enter rough, unstructured ideas, or difficult to take those ideas and create a more formal plan.

Waypoint addresses three important shortcomings of other tools:

- Data entry should be quick

- Comparisons should be easy

- Unstructured data is just as important as structured data

In short, I wanted an app where I could jot down loose notes about places I was interested in visiting, visualize different routes and gradually narrow it all down into an actual itinerary.

The interface I landed on has two panels: a text editor on the left and a map on the right.

One common task when planning a trip is gathering a list of locations you’re interested in visiting.

The simplest solution is using a normal text editor. Data entry is quick; the only real limiting factor is how fast you can type. The obvious drawback is that locations are displayed textually rather than plotted on a map, obscuring any spatial relationship between them.

The only dedicated tool for this that I really know of is Google’s My Maps  About - Google Maps Discover the world with Google Maps. Experience Street View, 3D Mapping, turn-by-turn directions, indoor maps and more across your devices.

About - Google Maps Discover the world with Google Maps. Experience Street View, 3D Mapping, turn-by-turn directions, indoor maps and more across your devices.

In Waypoint, the main interactive component is a rich text editor.

You use it just as you would Google Docs or Microsoft Word — type notes, add some formatting, cut and paste lines to rearrange your thoughts.

Adding a location is as easy as typing its name, using an @mention-style autocomplete inspired by Embark.

Characters show up as quickly as you can type them, and any changes are reflected instantly on the map view beside the document.

Even when apps make data entry easy, that data is often transient, making it difficult to see comparisons.

For example, if you want to see where two locations are relative to each other in Apple or Google Maps, you’re forced to use the navigation feature to create a route between them. And only one route is visible at a time — to see a different set of locations, you need to clear the route you’re currently looking at. This makes it very difficult to, say, determine which of a group of locations are near each other in order to cluster them on different days of an itinerary.

In Waypoint, every location is plotted on a map, so you always have a bird’s eye view of your trip.

To show routes, you can create a “route list” by beginning a line with ~ (just as you would with - for a bulleted list, or 1. for a numbered list).

Every location in the list has a route drawn between its marker on the map and the next one.

By default, the routes are the driving directions between the two locations, but you can toggle between that and a straight line by clicking on the location name and unchecking “Navigate”.

It’s easy to add, remove and rearrange locations in the route: just use the text editing commands you already know to edit the list, and the map automatically updates! To compare two routes, you can just copy and paste the whole list and rearrange as you see fit.

A bird’s eye view is nice, but sometimes you want to “zoom in” on a subset of your work.

To accommodate this, Waypoint also includes a focus mode — inspired by iA Writer  Focus Mode – iA Shut down distractions. Focus on the sentence or paragraph you're currently working on.

Focus Mode – iA Shut down distractions. Focus on the sentence or paragraph you're currently working on. ia.net/writer/support/editor/focus-mode — which dims all paragraphs other than the one under your text cursor.

On the map, Waypoint only shows the locations and routes in that paragraph.

Together, these features enable a powerful workflow: make a route list, copy and paste it below, alter the second list, enable focus mode and move your cursor between the two to quickly see the difference between them. No other tool I tried made this nearly as quick or as easy.

Under the Hood

At a glance, Waypoint isn’t too different from your average single-page app:

- The website as a whole is built with SvelteKit

SvelteKit • Web development, streamlined SvelteKit is the official Svelte application framework

SvelteKit • Web development, streamlined SvelteKit is the official Svelte application framework  kit.svelte.dev .

kit.svelte.dev . - Custom widgets such as tooltips and dropdowns use the Shoelace

Shoelace: A forward-thinking library of web components. Hand-crafted custom elements for any occasion.

Shoelace: A forward-thinking library of web components. Hand-crafted custom elements for any occasion. shoelace.style web component library.

- The rich text editor is built atop the excellent ProseMirror

ProseMirror In-browser structured text editing component

ProseMirror In-browser structured text editing component prosemirror.net toolkit.

- The maps and location search are powered by Stadia Maps

Stadia Maps: Location APIs for humans. Location APIs for humans: map tiles, static map images, routing, geocoding and search for every app.

Stadia Maps: Location APIs for humans. Location APIs for humans: map tiles, static map images, routing, geocoding and search for every app.  stadiamaps.com and the open source MapLibre GL JS

stadiamaps.com and the open source MapLibre GL JS  MapLibre

MapLibre maplibre.org library.

- Data is stored on the client using the Yjs Yjs Shared Editing

yjs.dev CRDT library.

yjs.dev CRDT library.

Hold up — that last one seems kinda weird?

It’s actually the key difference between Waypoint and a traditional single-page app. Rather than storing data on a server using a database like MySQL or Postgres, Waypoint is a local-first app that stores its data on the client using a CRDT.

(Some brief exposition: CRDTs are data structures that can be stored on different computers and are guaranteed to eventually converge upon the same state.

For a fuller explanation, check out my article An Interactive Intro to CRDTs  An Interactive Intro to CRDTs | jakelazaroff.com CRDTs don't have to be all academic papers and math jargon. Learn what CRDTs are and how they work through interactive visualizations and code samples.

An Interactive Intro to CRDTs | jakelazaroff.com CRDTs don't have to be all academic papers and math jargon. Learn what CRDTs are and how they work through interactive visualizations and code samples. jakelazaroff.com/words/an-interactive-intro-to-crdts/ , which breaks down the fundamental ideas behind CRDTs and how they work.)

CRDTs are often used to build collaborative experiences like you might see in Google Docs or Figma — except rather than requiring a centralized server to resolve conflicts, the clients can do it themselves. That decentralized sync allows the clients to store the canonical state of the data, rather than a copy fetched from a web server.

This approach confers some important benefits:

- Editing is instantaneous and synchronous. There are no loading spinners, no optimistic updates to roll back if a request fails and no “go online to save your changes”. The app is faster and more reliable to use, and much easier to develop.

- If I decide to stop hosting Waypoint, you’ll still have the file with your data. That file will work in any copy of Waypoint, without the need to set up special infrastructure.

That’s why this kind of app is called local-first. If you have the app and you have your data, you can still work on it — even if you’re not connected to the Internet or the developer has gone out of business.

All of this might seem like overkill for a personal app with a single user.

But I was planning this trip with my wife, Sarah, so Waypoint quickly needed realtime collaboration.

To address that, Waypoint uses a library called Y-Sweet  Y-Sweet Cloud: the WebSocket sync backend you’ll love

Y-Sweet Cloud: the WebSocket sync backend you’ll love ![]() y-sweet.cloud by Jamsocket

y-sweet.cloud by Jamsocket Jamsocket Give each user session its own dedicated backend.

jamsocket.com .

There are two parts to Y-Sweet:

@y-sweet/client: an npm package that gets included in the client-side bundle. This package is a Yjs “provider” — a plugin that syncs a Yjs document somewhere.- The Y-Sweet server: a websocket server that syncs documents between clients and persists them to S3.2

Architecturally, Y-Sweet acts as a bus en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bus_(computing) : clients connect to the Y-Sweet server rather than directly to each other. Whenever a client connects or makes changes, it syncs its local document with the Y-Sweet server. Y-Sweet merges the client’s document into its own copy, saves it to S3 and broadcasts updates to other clients. Since CRDTs are guaranteed to eventually converge on the same state, at the end of this process all clients have the same document.

This also makes it easy to share documents. Each Waypoint document is identified by a UUID. When a user opens a link with a given document’s UUID, their Waypoint client connects to Y-Sweet and tries to sync their local copy with Y-Sweet’s copy. If that user has never opened that document, they have no local copy, and the sync operation results in them just getting Y-Sweet’s copy in its entirety.

Here’s a diagram of Waypoint’s architecture after introducing Y-Sweet:

One reasonable objection here is that it looks an awful lot like a traditional client-server app — just replace Y-Sweet with a normal application server and S3 with a database. Doesn’t that defeat the whole purpose of local-first?

Ink & Switch addresses this in the case study of their Pushpin software  Pushpin: Towards Production-Quality Peer-to-Peer Collaboration Taking peer-to-peer beyond research prototypes, and working towards commercial-grade P2P collaboration software.

Pushpin: Towards Production-Quality Peer-to-Peer Collaboration Taking peer-to-peer beyond research prototypes, and working towards commercial-grade P2P collaboration software. www.inkandswitch.com/pushpin/#local-first-software :

Thus, in addition to local data storage on each device, the cross-device data synchronisation mechanism should also depend on servers to the least degree possible, and servers should avoid taking unnecessary responsibilities. Where servers are used, we want them to be as simple, generic, and fungible as possible, so that one unavailable server can easily be replaced by another. Further, these servers should ideally not be centralised: any user or organisation should be able to provide servers to serve their needs.

You can think of Y-Sweet as a “cloud peer”. Under the hood, it runs plain old stock Yjs — the exact same code that runs on the client. If you connected Waypoint to your own Y-Sweet server, there would be no discernible difference. To borrow Ink & Switch’s parlance: it’s “simple, generic, and fungible”.

Y-Sweet is one of two Yjs providers that Waypoint uses.

The other, called y-indexeddb Offline Support | Yjs Docs Adding offline support with y-indexeddb.

![]() docs.yjs.dev/getting-started/allowing-offline-editing , takes care of offline editing: it persists the Yjs document to the browser’s local IndexedDB storage.

Even if a user gets disconnected from the Internet, edits a document and then closes their browser, none of their work will be lost.

docs.yjs.dev/getting-started/allowing-offline-editing , takes care of offline editing: it persists the Yjs document to the browser’s local IndexedDB storage.

Even if a user gets disconnected from the Internet, edits a document and then closes their browser, none of their work will be lost.

Is It Local-First?

A popular question lately: what actually counts as local-first?

My mantra is “if the client has the canonical copy of the data, it’s local-first”.3

But Ink & Switch formalizes this with seven proposed ideals  Local-first software: You own your data, in spite of the cloud A new generation of collaborative software that allows users to retain ownership of their data.

Local-first software: You own your data, in spite of the cloud A new generation of collaborative software that allows users to retain ownership of their data. www.inkandswitch.com/local-first/ .

Let’s see how Waypoint stacks up:

- No spinners: your work at your fingertips. While Waypoint’s location autocomplete and map are subject to network latency, editing the document itself happens instantly. Verdict: yes.

- Your work is not trapped on one device. By simply visiting a link, you can load a Waypoint document written anywhere. Plus, you can download your data and open it in any given Waypoint instance. Verdict: yes.

- The network is optional. Again, other than the autocomplete and map, Waypoint is fully functional offline. Verdict: yes.

- Seamless collaboration with your colleagues. Waypoint supports both realtime and asynchronous collaboration, using a CRDT to resolve conflicts. Verdict: yes.

- The long now. Although Y-Sweet is a generic server, autocomplete and maps use a proprietary service called StadiaMaps. However, documents can still be viewed without requiring outside infrastructure. Verdict: sorta.

- Security and privacy by default. Y-Sweet stores copies of documents unencrypted in an S3 bucket. Verdict: no.

- You retain ultimate ownership and control. The canonical copies of data are stored on the client, with no limitations enforced by the server. Verdict: yes.

Five “yes”, one “sorta” and one “no”. Keep in mind that all the relevant technologies are off-the-shelf; most of these capabilities came for free by choosing Yjs (although any given CRDT library would have worked similarly) and Y-Sweet. Not bad!

Takeaways

Okay, so what did I learn?

Most importantly, local-first is not some pie-in-the-sky dream architecture. Although there are still problems to be worked out,4 it’s very possible to build a useful local-first app, today, with existing tools.

It helps a lot that various libraries in the ecosystem compose well.

Just snapping together ProseMirror, Yjs and Y-Sweet gave me a collaborative rich text editor with shared cursors.

Adding in yjs-indexeddb made it work offline.

This was all mostly out of the box, with very little setup; the degree to which everything Just Works is impressive.

That said, I think this is a best-case scenario — text editors seem to be the most “plug and play” genre of local-first app. But in general, the building blocks all fit together nicely.

The same can’t be said of Svelte — or, presumably, frontend JavaScript frameworks in general — which needed some massaging to work with Yjs.

To determine when to re-render, “reactive” frameworks like Svelte and Solid track property access using Proxies  Proxy - JavaScript | MDN The Proxy object enables you to create a proxy for another object, which can intercept and redefine fundamental operations for that object.

Proxy - JavaScript | MDN The Proxy object enables you to create a proxy for another object, which can intercept and redefine fundamental operations for that object. ![]() developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Global_Objects/Proxy , whereas “immutable” frameworks like React rely on object identity.

A Yjs document is a class instance that mutates its internal state, which doesn’t play well with either paradigm.

To have Svelte re-render when the document changed, I had to trick it into invalidating its state:

developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Global_Objects/Proxy , whereas “immutable” frameworks like React rely on object identity.

A Yjs document is a class instance that mutates its internal state, which doesn’t play well with either paradigm.

To have Svelte re-render when the document changed, I had to trick it into invalidating its state:

let ydoc = $state(new YDoc());

// HACK: the yjs doc is mutated internally, so we need to manually invalidate the reactive variable

let outline = $state(this.ydoc.getXmlFragment("outline"));

ydoc.on("update", () => {

outline = undefined;

outline = this.ydoc.getXmlFragment("outline");

});

Even so, in a lot of ways the developer experience was still much better than in a traditional single-page app. Here’s (roughly) the code to update the document title:

let title = $state("" + ydoc.getText("title"));

function setTitle(next: string) {

const text = ydoc.getText("title");

text.delete(0, text.length);

text.insert(0, next);

title = next;

}

Sure, there’s some weird CRDT-related boilerplate, but still: no async function, no try…catch, no worrying about the server.

I just set the title and move on with my life; Yjs will worry about syncing it in the background.

That might sound like magic, but I think it’s just a natural consequence of a fundamentally better abstraction. Using a local-first architecture rather than client-server promises to dramatically simplify single-page apps.

I was dreading adding offline support, but it turned out to be surprisingly easy.

SvelteKit supports service workers out of the box, and the documentation even provides some example code  Service workers • Docs • SvelteKit

Service workers • Docs • SvelteKit ![]() kit.svelte.dev/docs/service-workers as a starting point.

It wasn’t perfect, but it got me probably 95% of the way there — I could load any document I’d already opened, even without an Internet connection.

And as far as saving edits made offline, integrating

kit.svelte.dev/docs/service-workers as a starting point.

It wasn’t perfect, but it got me probably 95% of the way there — I could load any document I’d already opened, even without an Internet connection.

And as far as saving edits made offline, integrating y-indexeddb took one single line of code.

Dive In

I hope you enjoyed this! I had a lot of fun building Waypoint. This was my first hands-on foray into the local-first ecosystem, and it turned out to be a lot smoother than I anticipated.

If you want to see the code behind this explanation, you can find it on GitHub GitHub - jakelazaroff/waypoint Contribute to jakelazaroff/waypoint development by creating an account on GitHub.

github.com/jakelazaroff/waypoint .

Footnotes

-

We did end up using Wanderlog

Wanderlog travel planner: free vacation planner and itinerary app Plan your road trip or vacation with the best free itinerary and road trip planner. Wanderlog lets you to make itineraries with friends, mark routes, and optimize maps — on web or mobile app

Wanderlog travel planner: free vacation planner and itinerary app Plan your road trip or vacation with the best free itinerary and road trip planner. Wanderlog lets you to make itineraries with friends, mark routes, and optimize maps — on web or mobile app  wanderlog.com once we had our itinerary.

The mobile app is buggy, but its ability to automatically import tickets and confirmations from our email and save them for offline access was incredibly useful. ↩

wanderlog.com once we had our itinerary.

The mobile app is buggy, but its ability to automatically import tickets and confirmations from our email and save them for offline access was incredibly useful. ↩ -

This is a slight oversimplification describing the managed version of Y-Sweet. For Waypoint, I self-hosted Y-Sweet

y-sweet/docs/running.md at main · jamsocket/y-sweet A standalone yjs server with persistence to S3 or filesystem. - jamsocket/y-sweet

github.com/jamsocket/y-sweet/blob/main/docs/running.md , which involves running the Y-Sweet server on a Cloudflare Worker and using a small server-side library within SvelteKit to negotiate the connection. ↩

-

Technically, if the client has have the canonical copy of the data but never sends it over the network, it’s not really local-first — just local. I explore this dynamic more in The Website vs. Web App Dichotomy Doesn’t Exist

The Website vs. Web App Dichotomy Doesn't Exist | jakelazaroff.com A one-dimensional spectrum can't sufficiently capture the tradeoffs involved in web development.

The Website vs. Web App Dichotomy Doesn't Exist | jakelazaroff.com A one-dimensional spectrum can't sufficiently capture the tradeoffs involved in web development. jakelazaroff.com/words/the-website-vs-web-app-dichotomy-doesnt-exist/ . ↩

-

One such problem is access control, which I did not attempt to address with Waypoint. Ink & Switch has an ongoing project called Beehive

Beehive lab notebook: Local-first access control Local-first access control

Beehive lab notebook: Local-first access control Local-first access control www.inkandswitch.com/beehive/notebook/ exploring approaches to solving this. ↩